都市と農村の新しい関係性によせて

Reimagining the Urban–Rural Relationship

都市デザイナー

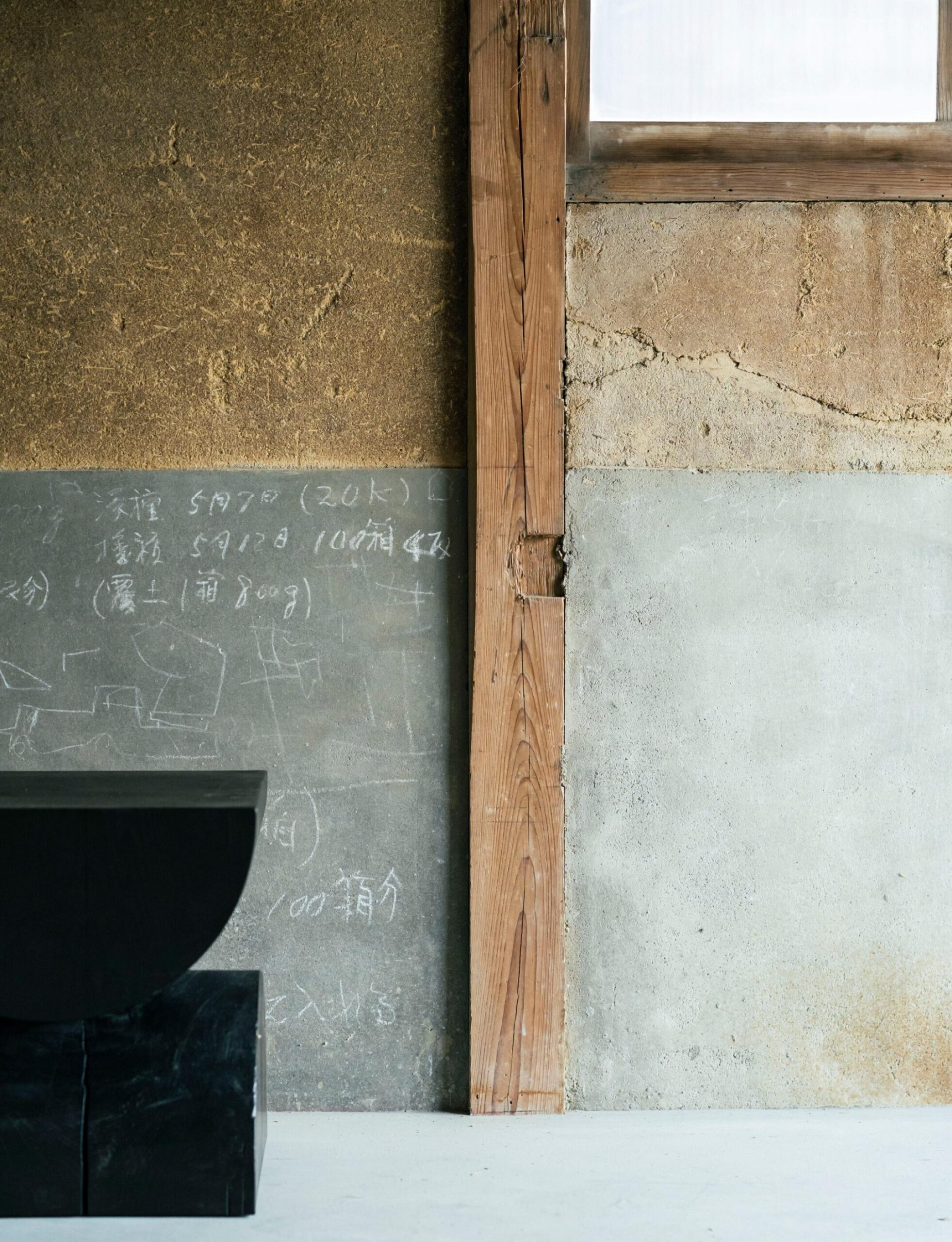

Photograph

Urban Designer

Photograph

ブーーーーーーン、という、草刈りの音がどこかから聞こえてくる。株式会社マガザンの打表・岩崎さんが「子供の頃、”退屈の象徴”だった」と言っていた、その音。その感覚は、私にもなんとなく分かる。ミュージアムもカフェもショッピングモールも近くにはなくて、ただただ田んぼに囲まれた、家族との暮らし。毎日が同じ風景で、何をしようかなあ、何もないなあなんて思いながら、窓からぼんやり外に目をやり、雑誌やテレビでみる遠い都会の生活に思いを馳せる。地方出身の人なら、誰もがなんとなく共有できる子供時代の感覚なんじゃないだろうか。

Bzzzzzzzzzz – the sound of a lawn mower can be heard from somewhere. That sound which Mr. Iwasaki, an executive at Magazan Co., Ltd., said “was the symbol of boredom” in his childhood. I can somehow relate to that feeling. With no museums, cafes, or shopping malls nearby, just a life with family surrounded by rice fields. Every day with the same scenery, awkwardly thinking “what should I do?” and “there’s nothing here,” gazing absently out the window while dreaming of distant city life seen in magazines and on TV. Isn’t this childhood sensation something that anyone from rural areas can somehow relate to?

岩崎さんは、兵庫県三木市久留美地区出身で、小さな山田錦農家の長男として育った。彼と出会ったのは、私が京都に引っ越してきた6年ほど前のこと。カルチャー好きで、今のトレンドや面白い人たちに囲まれている、都会的なお兄さんという印象は当時も今も変わらない。2年ほど前に「実家の稲刈りに来ない?」と誘われて三木市にはじめて訪れ、岩崎さんの実家が自然に囲まれた農家であるということを知った。酒米「山田錦」を作っている地域らしく、この稲刈りの日も、美味しいお酒を片手にほくほく帰宅したことを覚えている。

Mr. Iwasaki grew up as the eldest son of a small Yamada Nishiki rice farming family in the Kurumi district of Miki City, Hyogo Prefecture. I met him about 6 years ago when I moved to Kyoto. My impression of him as a culture-loving, urban-type person surrounded by current trends and interesting people hasn’t changed from then until now. About two years ago, when he invited me saying “Would you like to come help with the rice harvest at my family home?”, I visited Miki City for the first time and learned that his family home was a farm surrounded by nature. As you might expect from a region that produces “Yamada Nishiki” sake rice, I remember returning home contentedly that harvest day with a delicious drink in hand.

それから、会うたびに「最近は思考の90%が実家」という話を聞いていて、あれよあれよという間にクラウドファンディングが立ち上がっており、稲刈りの際に見せてもらった築100年に迫る実家の建物も気づくと綺麗にリノベーションされていて、宿泊施設「[Social Rice Farm 心拍(しんぱく)]がオープンしていた。農や酒、食や文化風土に興味を持った人のための、農業体験もできる拠点で、これからの「農」のあり方を模索する事業であるという。

プレオープン後、いち早く宿泊させてもらった。あの「ブーーーーーーーーーン」という草刈機の音を聞きながら、彼が幼少期に見ていたであろう景色を同じ窓から眺めながら、この文章を書いている。

Since then, every time we met, he would tell me that “lately, 90% of my thoughts are about my family home,” and before I knew it, a crowdfunding campaign had launched, and the nearly 100-year-old family home I had seen during the rice harvest had been beautifully renovated and opened as an accommodation facility called “[Social Rice Farm Shinpaku].” It’s a hub for people interested in agriculture, sake, food, and cultural climate, where you can experience farming, and it’s a venture exploring what the future of “agriculture” should look like.

After the pre-opening, I was among the first to stay there. I’m writing this article while listening to that “Bzzzzzzzz” sound of the lawn mower, looking out from the same window at what must have been the view he saw in his childhood.

変わる都市、変わる田舎

Urban and Rural Transformations

大人になってから田舎の良さを再発見したり、Uターン移住・起業自体は、よく聞く話かもしれない。けれど最近はまた少し、都会と田舎を取り巻く環境について、事情が変化しているような気もする。どういうことかというと、田舎のこれからを考えることは、逆に都市を考えることでもある、と私は思うのだ。

柳田国男の著書に『都市と農村』というものがある。昭和初期、農政官としてのキャリアを築いた柳田は、農村の疲弊と農民の貧困を、農村内部の問題としてではなく、都市との関係でいち早くとらえた。

郊外化とインターネット技術の進んだ現代では、両者の境界も非常に曖昧なものになってきている。”都市なるもの”と”田舎なるもの”の境界を曖昧なものとして捉え、横断的な概念化と研究をいち早く行ったのが、建築家・レム・コールハースの一連の都市研究、その後のカントリーサイド研究だ。2020年には、ニューヨークのグッゲンハイム美術館で、カントリーサイド=「田舎」をテーマとする展覧会「Countryside, The Future」が行われた。背景には、世界的に都市化が進むなか、「じつは都市以上の大きな変化が、近過去から現在に至るまでの田舎では起こっているのではないか?」という問いがある。

やや話をややこしくしてしまった。つまり、これからの「農」「田舎」「地方」を考えることは、これからの都市を、そこでの私たちのライフスタイルをも巻き込んだ問いに繋がるものだということを伝えたい。都会の人たちが週末に稲刈りをするために泊まりにくる「心拍」という場所の面白みも、ここにあるような気がしている。

While rediscovering the charm of rural life as an adult or returning home to start a business might be a common story, I feel there’s been a subtle shift lately in the dynamics between urban and rural environments. What I mean is that thinking about the future of rural areas is, conversely, also a way of thinking about cities.

There’s a book by Kunio Yanagita called “Cities and Villages.” In the early Showa period, Yanagita, who built his career as an agricultural policy official, was one of the first to view rural decline and farmer poverty not as internal rural issues, but in relation to cities.

In our modern era of suburbanization and advanced internet technology, the boundaries between the two have become increasingly blurred. Architect Rem Koolhaas was among the first to approach this ambiguous boundary between “the urban” and “the rural,” conducting cross-cutting conceptualization and research through his urban studies and subsequent countryside research. In 2020, the Guggenheim Museum in New York hosted an exhibition titled “Countryside, The Future” themed around countryside = “rural areas.” Behind this lies the question: “In fact, hasn’t the countryside undergone even greater changes than cities from the recent past to the present?” amid global urbanization.

I’ve made this somewhat complicated. What I want to convey is that thinking about the future of “agriculture,” “rural areas,” and “regions” leads to questions that encompass the future of cities and our lifestyles within them. I feel this is where the appeal lies in “Shinpaku,” a place where urban dwellers come to stay on weekends for rice harvesting.

つくることと食べることと住まうことと

施設の目の前には小さな畑があって、にんじんや白菜、大根が生えている。数ヶ月前、稲刈りの時期にここにきたときには違った種類の野菜が生えていて、ギョッとするほど豊作のキウイの木が庭にあるのが印象的だった(思わず、スーパーでこれだけのキウイを買ったら幾らになるのか計算してしまった)。

夕食どきに到着した私たちは、そのまま畑に出た。土からにんじんを数本引っこ抜き、白菜を刈り取ったとき、大地の匂いがふわりとする。泥を落として、そのまま室内のキッチンに持っていき、水洗いをして調理を始める。スーパーできちんとプラスチック包装されて値札がつけられた野菜とは違う、本来の食べ物の味がした。

Making, Eating, and Living

There’s a small field right in front of the facility where carrots, Chinese cabbage, and daikon radish are growing. When I came here several months ago during rice harvesting season, different vegetables were growing, and I was struck by the impressively abundant kiwi tree in the garden (I couldn’t help calculating how much it would cost to buy that many kiwis at the supermarket).

When we arrived around dinnertime, we went straight to the field. As we pulled up several carrots from the soil and harvested Chinese cabbage, the earthy scent wafted up. We brushed off the dirt, brought them straight to the kitchen inside, washed them, and began cooking. It tasted like real food, different from the vegetables at the supermarket that are neatly wrapped in plastic with price tags attached.

夜は、周囲の田んぼで収穫された山田錦を使って作られた日本酒を、贅沢にも数種類頂く。周囲の大地で育まれた米が酒になり、それがまた周囲の大地で作られた野菜たちと一緒に自分の身体に入ったとき、私自身の身体も周囲の一部になったような、不思議な感覚。これはクセになりそうだ。

At night, I indulged in several types of sake, luxuriously brewed from Yamada Nishiki rice harvested from the surrounding fields. When the rice, nurtured by the local land, was transformed into sake and entered my body alongside vegetables grown in the same soil, I felt as if I, too, had become a part of this place.

It was a strange yet deeply immersive sensation—one that I could easily get addicted to.

夜は、兵庫県神戸市北区淡河町を拠点に 伝統的な茅葺き屋根の修復工事を行う「くさかんむり」の相良育弥さんプロデュースの、稲わらベッドで贅沢な眠りを頂戴した。すっかり9時間ほど寝た後に目を覚ますと、先輩たちはもう起きて、畑から朝ごはんの野菜を収穫していた。

At night, I enjoyed a luxurious sleep on a straw bed produced by Ikuya Sagara of Kusakanmuri, a group based in Ogo Town, Kita Ward, Kobe City, that specializes in restoring traditional thatched roofs. After a solid nine hours of sleep, I woke up to find that my senior companions were already up, harvesting vegetables from the field for our breakfast.

黄金の田んぼで草刈りをして一汗かいたあと、軽トラにみんなで乗り込んで宿泊施設に帰るまでの10分でみた景色が忘れられない。

After breaking a sweat mowing grass in the golden rice fields, we all piled into a small truck and headed back to the lodging. Those ten minutes on the ride back—taking in the scenery—are something I’ll never forget.

農業を、地方を社会に開いた先にあるもの

私が生まれた東北は、この10年間で東京圏に20代の若者が13万人も流出したらしい。日本橋のビル群をスーツで歩いていると、自分が自分以上に大きな存在になれたような、清々しい気持ちになると、東北出身のある知人が言っていた。その気持ちも十分に分かるから、田舎に留まれ、田舎に帰れ、とは言えない。むしろ価値の転換は、一度都会に出た岩崎さんがこの場所で新しい事業をたち上げたように、風通しがよく変化を包容する土壌で起こる。だからむしろ、どんどん出て行っても良いのだと思う。

そのうえで、田舎も都会も両方知っている存在の尊さを知って欲しいなとは思う。そして、両者を行き来できるようなライフスタイルを志向してみてほしい。そのための拠点として、「心拍」には他の宿泊施設にはない価値があると思うのだ。

未来の家族単位で営まれる農業を社会に開き、日本中、世界中から農と酒の文化に参加できる新たな農業の形を、心拍では「共農共杯」と定義している。なんだか酒杯を持ち上げながら声をあげるような、縁起の良さと勢いがある。日本の農と、地方の未来は明るい。その対にある都市の未来も明るい。そう思わせてくれる、1泊2日の体験であった。

写真:市橋 正太郎

Beyond the Opening of Agriculture and the Countryside to the World

The Tohoku region, where I was born, has reportedly seen 130,000 young people in their twenties migrate to the Tokyo metropolitan area over the past decade. A friend from Tohoku once told me that walking through the skyscrapers of Nihonbashi in a suit makes them feel as if they have become something larger than themselves, filling them with a refreshing sense of fulfillment. I completely understand that feeling, so I can’t simply tell people to stay in their hometowns or return to the countryside.

In fact, shifts in values often happen in open and adaptable environments, like how Mr. Iwasaki, after spending time in the city, returned to this place to start a new business. That’s why I believe it’s perfectly fine for people to leave their hometowns and explore new places.

At the same time, I hope people come to appreciate the value of knowing both rural and urban life. I encourage them to pursue a lifestyle that allows them to move freely between the two. In that sense, *Shinpaku* offers a unique value as a base, something that other accommodations cannot provide.

At *Shinpaku*, we redefine a new form of agriculture called *Kyōnō Kyōhai*—a concept of “shared farming and shared toasting”—by opening up traditionally family-run farming to society and inviting people from across Japan and the world to engage with agricultural and sake culture. The phrase itself carries an uplifting, celebratory feel, as if raising a sake cup in a lively toast.

The future of Japanese agriculture and rural communities is bright. And so is the future of cities. This was the feeling I took away from my two-day, one-night experience.

都市デザイナー | 杉田まりこ

2016年ブリュッセル自由大学大学院アーバン・スタディーズ修了。2021年より都市体験のデザインスタジオ(一社)for Cities共同代表。都市や建築に関わるストーリーテリングをテーマにした出版レーベル「Traveling Circus of Urbanism」、建築家やアーティストの京都での滞在制作をサポートするアーバニスト・イン・レジデンス「Bridge Studio」を運営。都市・建築・まちづくり分野における執筆や編集、リサーチほか文化芸術分野でのキュレーションや新規プログラムのプロデュース、ディレクション、ファシリテーションなど国内外を横断しながら活動を行う。(一社)ホホホ座浄土寺座共同代表理事。

Urban Designer | Mariko Sugita

Mariko is an independent designer and researcher on architecture and urbanism based in Kyoto, Japan. She graduated from 4CITIES’ Euromaster in Urban Studies, which brought her to 4 cities in several countries across Europe (Brussels, Vienna, Copenhagen, and Madrid). She co-founded the urban experience design studio ‘for Cities’ in 2021, where she organizes place-making design projects across Japan and beyond. She owns the publishing label Traveling Circus of Urbanism, a platform for urban storytelling and research through traveling, and manages the cultural space Bridge To in Kyoto where she hosts an ‘urbanist in residence’ program. She loves to write, edit, research, curate, and facilitate new programs in the fields of cities, architecture, and urban development, especially through international cultural collaborations.

関連する記事

Related Story